I missed Winter Tide when it was first published—the simultaneous blessing/curse of working in publishing meaning that I am drowning in books at all times. I was excited to finally delve into Ruthanna Emrys’ debut novel, and not only am I glad I did so, but I’m hoping I get to the sequel a lot faster.

Because here is a book that understands the importance of books.

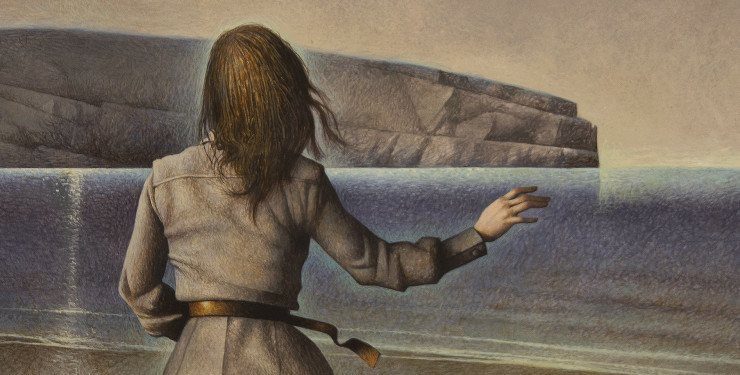

Buy the Book

Winter Tide

Lovecraft’s Mythos is particularly ripe for cultural commentary and exploration of otherness because the eldritch gods are themselves so deeply, horribly other. Especially since Lovecraft himself was so extra about his racism, it makes it all the more interesting to probe the racial assumptions, weirdness, and hatefulness in his work. Hence The Ballad of Black Tom, which tells a story of racist police violence wrapped up in a riff on “The Horror at Red Hook,” and Winter Tide, which casts worshipers of the Ancient Ones as an oppressed minority.

Winter Tide posits the citizens of Innsmouth as followers of eldritch gods, workers of magic, who have been violently repressed by the US government, which decides they’re cooking up un-American plots. To put a finer point on it, Emrys tells us that Aphra Marsh, her brother Caleb, and every other citizen of Innsmouth were rounded up and thrown into camps in the California desert in 1928. Twelve years later, the last surviving Innsmouth residents were joined by newly-incarcerated Japanese-Americans. Later, when Aphra works for the government, her contact is a Jewish man who faces discrimination now that hatred of Hitler has died down, and white, Christian America has fallen back into casual anti-Semitism.

Binding Aphra’s troubles to those from our own history, Emrys gives her pain even more weight, and is able to turn a sharp eye on the US’s other crimes of prejudice. And by focusing on Aphra’s loss of books, Emrys is able to comment on the way an oppressive power can remove a culture from its roots. Just as Britain robbed the Irish of their language and religious practice, white US and Australian governments stole indigenous children from their homes and forced foreign words into their mouths, and slavers stripped Africans’ names from them, so the U.S. government, in a fit of panic, ripped Aphra and her brother away from their (harmless) culture. As the book begins, they have come to realize that even with “freedom” from the camps, there is a gulf between them and their identities that may be unbridgeable.

The first 50 pages of Winter Tide have very little “plot”—they ignore action to focus instead on creating an expansive world, and telling us what sort of story we’re about to read. Aphra Marsh’s family, home, and culture have all been wiped out, but what does she miss?

She can’t think, at least not directly, about her mother, or her father, murdered before her eyes. She can’t dwell on the loss of her physical home, or her brother, 3,000 miles away, or the twenty years of youth stolen from her.

What she misses is books.

Because that was maybe the cruelest of the oppressions—her people were not allowed to read nor write. The camp guards were fearful of anything that might be used in a ritual, and the government was afraid she and her neighbors would call upon the Deep Ones, so for nearly twenty years Aphra Marsh was not allowed so much as a picture book. Her own family’s books, from copies of the Necronomicon to cookbooks, were confiscated and sold off to Miskatonic University, along with all the libraries of her neighbors. She tried to scratch the alphabet into the dirt for her little brother, but when we see a letter from him it’s apparent that his literacy isn’t much beyond an eight-year-old’s.

But Emrys gives us an even better, and far more heartrending, way to see the damage the camps have done. When we meet her, Aphra works in a bookstore with a man named Charlie Day. The bookstore is large and rambling, infused with the smell of sunshine, dust, and aging paper, and Aphra loves it. She is greedy, at all times, for the scent of books and ink, and for grazing her hands over spines as much as sitting down to devour stories. This is sweet, relatable to those of us with a similar book habit, but where it turns chilling is whenever a police office, a government agent, or a studiously bland man in a suit appears in the door of the shop: Aphra yanks her hands back. She shrinks into herself, expecting punishment, and utterly forgetting that she’s an employee of the shop, with more right to be there than anyone but Mr. Day himself. It’s horrible to see, repeatedly, how the torture of the camp defines and warps her relationship to the thing she loves most.

Later, when Aphra travels to Miskatonic U herself to delve into her family’s books, it’s crushing to see her and her furious brother forced to beg a librarian for access to their own property. As they sift through books, they find neighbor’s names, the marginalia of the children they should have grown up with, and, finally, their own mother’s handwriting. They both know it on sight. I’ll confess I wouldn’t recognize my mother’s handwriting—but I’ve never needed to—so it is especially poignant to see them grab so tightly to their memories, and to this tangible connection to their past. They’ve been looking for their people’s words for so long.

Even as the plot unspools, and tensions between the government and the newly active “Aeonists” ratchet up, the book’s action centers on a library. The plot hinges largely on gaining access to it, trying to break into it, all the while wrestling, physically and spiritually, with the idea that the people of Miskatonic are holding on to an intellectual treasure that is not theirs to hold. The library itself is spoken of in the hushed tones usually reserved for a cathedral:

Crowther Library loomed in silhouette, more obviously a fortress than in daylight hours. Crenellations and ornate towers stretched above bare oak branches. Windows glinted like eyes. The walls looked ancient, malignant, made smug by the hoard of knowledge cloistered within.

And even during a daring raid on the building, Aphra pauses to remember a moment from her brother’s childhood:

As tradition bade, he’d received a fine new journal and pen for his sixth birthday. I remembered him holding them proudly, sitting poised with nib above paper for minutes on end as he considered what words might be worthy.

This love of the written word, and reverence for books, pervades Emrys’ entire story—but she doesn’t neglect the other side, and when an otherworldly being chooses to punish a mortal, they do it not by taking her sanity or her life, but by rendering her illiterate.

I’m not as familiar with the Lovecraftian Mythos as some writers on this site (Emrys included!). But having read Winter Tide, what I’ve come away with is the beauty of a book that honors literary culture, considers reading as a birthright, and delves into horror with a group of unabashed book nerds as heroes.

Leah Schnelbach knows that as soon as this TBR Stack is defeated, another will rise in its place. Come give her reading suggestions on Twitter!

Ursula LeGuin also dealt with the erasure of culture by means of the eradication of literature in The Telling.

Ruthanna Emrys also wrote The Litany of Earth, a little prequel/worldbuilding short story that’s well worth the read. And I can’t wait for the next book to come.

Loved it and my knitted Yith is watching over my office.

It had been years since I could point to just one book and say it was my favorite. After reading, and rereading Winter Tide, it is absolutely my favorite book. I love the characters and the worldbuilding and the way it turns Lovecraft’s xenophobia on its head.

Have you read LOVECRAFT COUNTRY by Matt Ruff? Also deliciously expanding the Mythos while remodeling it.

On a side note, I also think it’s great that a book like this was written by someone who shares a name with Merlin. :)